So ya want to be a military collector, eh?

Guidelines for the New Military Collector

Sponsored by the Calgary Military Historical Society

by David W. Love 2012

Reproduction or copying of any contents of this article, by any means, for commercial or personal gain, is prohibited without the express written consent of the author and then only with proper acknowledgement. Reproduction or copying for purely personal use is allowed.

Table of Contents

The Military Collecting Environment

Evolution of the Average Collector

Specialization vs. Generalization

Artifact Sources and Networking

Variations in Military Artifacts

Factors affecting costs and identification criteria

Manufacturing methods, materials, variations

Catalogue Identification Conventions

Preservation and Conservation of Military Artifacts

Framing and Mounting Your Collection

Formal Display of Your Collection

Significant Canadian and International Military Collectors’ Societies

Significant Museums, Archives and Libraries Having Military Collections

Selected Bibliography of Standard (Popular) Military Collecting References

Introduction

Let me start with a word of warning! Once you decide to join the ranks of enthusiastic military collectors, you are in immediate danger of contracting a 'disease' which, although not fatal, may well become obsessional. If allowed to go unchecked, this can quickly become epidemic with little chance of cure. So guard against this and approach the subject with care and method.

War has always been, and always will be, an evil force, but no matter how man strives to control his aggressive feeling and for all his intellect and veneer of civilization, that indefinable instinct seems to explode and overflow from time to time. Through the ages there have been many bloody wars and battles, and the paraphernalia of these conflicts make for an interesting study. Hence the great interest in all matters pertaining to the military.

Any appreciation of history will quickly give some idea of the potential scope of military collecting. The field of military collecting is vast. The military collector can, through his/her hobby, journey through a strange and wonderful world crowded with items that can be traced far back into the annals of history. With each new piece obtained, whether it is a mere brass button, cap badge or faded photograph, a little more is learned of the complex history of militaria. Using the Canadian experience alone by way of example (a relatively narrow and short-lived focus when compared to the military experience of other countries — but ours nonetheless), the combination of authorized and unofficial Volunteer, Militia and Permanent Force units, their establishments, disbandments, re-establishments, reorganizations, amalgamations, the advancement of technology and modernization, the passage of time and the universality of the military presence (most every Canadian community of any size has had a military presence of some sort), have all combined to produce a veritable wealth of potential collectibles. And this is just Canada. The variety of military artifacts worldwide boggles the mind and is only limited by the imagination of the individual collector. Items of such magnitude as tanks, artillery and vehicles vie with such triviata as buttons and crests (yes, there are individuals who collect all of these). Items of small intrinsic value compete for the affections of collectors with artifacts of high material worth. The exotic contends with the common. In addition, there are scores of other related items. Disabled groups, veterans’ organizations and other interest groups regularly issue material of various shapes, sizes and types, not to mention the related activities of society as a whole. As a result of all this, the oft-used phrase, “one man’s garbage is another man’s treasure” readily comes to mind here. The variety is available for any taste or inclination.

Despite the above and while becoming increasingly harder to do, military collecting can still be, by present-day standards and some constraint, a comparatively inexpensive hobby, unless the collector seeks the rarer examples. For example, cloth insignia or buttons are probably the cheapest of all, and more modern examples are plentiful and make an attractive display. It is still possible to gather together a decent collection at relatively little expense. To the general public, military items, especially the smaller examples, are still largely regarded as commonplace, and at garage sales, flea markets and similar events, they may still be had at quite reasonable prices. Any veteran collector can usually cite several examples where he was able to procure something of value for very little cash outlay. Then, of course, there is the added expedient of trading with other collectors to keep costs in check. Certainly though, the corollary is always present whereby it is very easy to quickly move your collection into the lofty heights of a significant investment.

The choice is yours though — no one else's. The potential field is vast and always-changing, and there is something for every pocketbook. These are the intrinsic beauties of this hobby.

Common Categories of Military Collecting

- Ammunition - small arms, artillery, infantry, armoured

- Art - original, prints, lithographs, trench art

- Buttons

- Cloth Insignia - shoulder flashes, unit patches, commemorative flashes

- Edged Weapons - swords, bayonets, knives

- Firearms - rifles, muskets, handguns, automatic weapons*

- Instruments and equipment- survey, navigation, communication, medical, etc.

- Medals - gallantry, service, campaign, tribute (e.g. homecoming, veterans recognition)

- Metal Insignia - headdress, collar, shoulder, belt

- Paper artifacts - letters, stamps, envelopes, propaganda, passes, postcards, military money, etc.

- Personal items - toiletries, cutlery, condoms, ration cards, etc.

- Photographs and prints

- Re-enactments – i.e. a need for period clothing and equipment

- Sweetheart brooches

- Uniforms and accessories - kit, webbing, packs, helmets, headdress, etc.

- Vehicles - soft skinned, armoured, specialty

- Miscellaneous - anything else that can be imagined but not included above

*Given the new and ever-tightening/changing government regulations in Canada regarding firearms and other weapons, it behooves the potential collector to carefully consider this avenue of military collecting before entering into it. Increasingly also, due to continuing violence involving firearms, politically this may not be an area to consider.

This booklet was originally compiled and handed out in 1992 as an accompaniment to a public display developed by The Calgary Military Historical Society. Using the annual national convention of the Military Collectors’ Club of Canada as a venue, the objective of the display was to provide some insights into the hobby of military collecting as well as supply some information on the Calgary Military Historical Society. The material contained within this booklet is the result of experiences gained through forty years of collecting experience by this author personally and that of other members of the Calgary Military Historical Society.

Although this document attempts to give practical information to the new military collector and interested individual, it can by no means cover all topics. To do this would be almost an impossible task. Because of this and for sake of expediency, it will discuss what is felt to be some of the major points in the hobby. It will also primarily concern itself with the Canadian scene, and in particular the fields of medal and insignia collecting. While it is recognized there are a vast number of individuals out there who have other broader interests, this booklet is seen as an overview rather than a definitive presentation. Notwithstanding this, it should be noted that certain truisms of military collecting exist regardless of any specific focus. Hopefully, many of these will be captured in the following discussion. Many of the more specific details are left to your joy of discovery as you pursue your hobby. As a final aside, you will find an appendix attached listing some further information which should assist the newcomer in this exciting hobby.

As one last aside, in order not to overlook any individual or company, or create any undue bias, no dealers, auction houses, or others who are in the ‘business of military collecting’, nor any specific artifact pricing will be recommended here. This will be left to you, the individual, to determine based on your own personal experiences and your circle of collecting contacts. Ultimately, most everything any collector learns is a evolutionary matter directly relating to the accumulation of personal experiences as the hobby is pursued. Now saying that, it is the author’s hope that this article will provide a practical accompanying framework and guide in developing this experience. Happy collecting!

The Military Collecting Environment

Military artifacts come in a near-infinite variety of shapes, sizes and materials. Military collectors too are equally varied and come from every walk and station in life. It is safe to assume that for any particular type of artifact, you can be sure there are active collectors in competition for them. Most families in Canada have some sort of military experience in their history and it is quite possible one of your neighbours has more than a passing interest. The hunt is carried from many fronts and is usually keen.

Some collectors will spend a life-time searching for a particular item. Others will collect almost anything with a military flavour, filling their den, study or home with all manner of strange and varied items, often to the despair of a tolerant and ever-patient spouse. To be a collector of anything is a visible mark of idiosyncrasy, so those about to march into the strange world of military collecting should get used to the odd looks and comments of strangers, friends and relations!

From the perspective of numbers alone, and once again using only the Canadian experience, serious military collectors and other interested individuals number in the thousands (the same can be also be said of many other countries). Attached to each of these individuals are collections of varying size and quality, many of which are the envy of museums. Given that there are only about one hundred thirty museums in Canada with any sort of a military collection, one can quickly see where the majority of this collected material lies. However this very large collecting fraternity tends to reside outside the formal museum environment and, as such, is generally unadvertised.

While almost any Canadian community of consequence, has one or more military collectors, the collecting fraternity is close. Arising from this large population of similarly-focused individuals is a surprisingly intimate network kept alive through a very active and continuing correspondence. This network is seen to be both informal through personal contacts and formal through membership in collecting organizations. The result is a close-knit community based upon friendship, trust and shared interests. But what is the glue that keeps this phenomena viable? Simply put, it is the personal integrity of each individual collector.

The collecting fraternity is ultimately based upon the tenets of personal reputation. Nothing else is more important – period! Because of the intimacy of the collecting fraternity, the knowledge of any instance of unethical or improper behaviour towards fellow collectors can circulate very quickly. When that happens, and depending on the severity of the indiscretion, the collecting community could ostracize you just as quickly. At the very least you will have destroyed, in part, the trust that exists within your immediate circle of contacts. This idea of ethical behaviour includes not only honesty but also fairness of action, and commitment to agreements and understandings between individuals. As one example, a collector buys an item from another with an understanding that the former owner will be given first right of refusal should the article be available for sale in the future. Hard feelings may develop if the buyer, for whatever reason (and it may be as innocent as forgetfulness), sells the item without first offering it back to the original owner. At the very least, dealing with the former owner will be more tenuous in the future. In the foregoing, nothing illegal or inherently dishonest was present, but the understanding or agreement was not met. Keep track of these commitments and honour them, and always try to treat your collecting colleagues in a manner that you yourself would wish to be treated. An old notion perhaps — the Golden Rule — but nonetheless a cornerstone of the collecting world.

Evolution of the Average Collector

While each collector is as unique as the items being collected, and while each starts upon this hobby in different ways, it is safe to assume something of a specific motivational nature started the individual on this course. Many collectors can identify the exact start of their collecting experience. It could be the discovery of a relative’s military souvenirs, awards or belongings dating from some past service, or the interest of a parent. An article of design catches the aesthetic eye or an affinity develops through personal military or related service. Regardless of motivational differences and the varied background of each individual, it is interesting that almost all tend to pass through a similar evolution in their hobby.

Upon entering the field, an individual generally has limited knowledge on the subject and little enlightenment towards the collecting fraternity. This is nothing to be ashamed of, if one is willing to learn. Collecting at this stage manifests itself by purchases from readily visible sources such as flea markets, dealers or the occasional public collecting show. Trading tends to be rare and generally buying is frequent, uninformed and without any real sense of purpose or focused direction. While cost is a consideration, it is generally less important at this stage as the fair market value of acquisitions is not really understood. One could say that a "shotgun" approach of collecting is followed — that is, if you like it and can afford it, you purchase it. While being without clear objectives, this is nonetheless valuable as it serves to build up inventory rather quickly and, more importantly, you learn as you go. Over a variable period of time, ranging from months to years, with the realizations of an ever-shrinking wallet and the tremendous variety of supply, and greater insight in possibilities, the collector gains an appreciation that not everything can be acquired. Therefore he/she becomes more discriminating in interest. As with the early formative years of a child’s development, this represents the period of greatest growth in knowledge and experience.

Usually at some point, the collector evolves to the second stage of development — a formal narrowing or specialization of interests. Here again, individuals still tend to be somewhat limited in their knowledge of their chosen focus, but this is due more to the depth of investigation they will now undertake rather than an ignorance of the subject in general. The main difference from the first stage is that they now have in place reciprocal networks with other collectors and dealers, and have discovered pertinent reference and artifact sources within the collecting fraternity. They understand where to gain the needed knowledge and which questions need to be asked. In short, they understand the game.

The final or mature stage in a collector's life is that of an expert in a chosen specialty who is quite particular and very focused to the direction his/her hobby is going. It is in this stage that the best collections develop. Besides a longer tenure in the hobby, the individual is now very comfortable with a focus of interest and is acknowledged by others as a source of information on his specialty. The knowledge level is usually of high calibre and quite extensive — comparable in many cases to that expected of university academics and professional historians.

Of course, the above is often confused by the tendency of collectors to change their focus from time to time, and therefore many can be seen to simultaneously reside in the second and third stages as they gain knowledge in new directions. However this only builds on an already-impressive base of wisdom which any new collector should avail themselves of, given the chance. Remember it is not a reflection on your character to ask questions of individuals having more knowledge in a particular area. You gain some understanding, and just perhaps, initiate what could become a very rewarding and lasting friendship.

Specialization vs. Generalization

The question often arises among collectors about the relative merits of specialization vs. generalization. Initially, although you may have already determined to focus your sphere of activity, it is probably best to collect anything you can find at a reasonable price, or that you can obtain from friends, as those items you do not need for your own collection can be traded later with other collectors. In this way, a newly-established collection can be built to a point of personal satisfaction and credibility. This also serves to clarify your choice of focus as being realistic and attainable (most collectors strive for a “complete” collection in one or more areas). You gain experience. You gain knowledge in a variety of areas. As mentioned though, considerations of limited resources and a rapid realization that one individual cannot adequately or realistically cover all available avenues, ultimately leads the average collector to focus his/her interests. But just to say a collector is specializing can be somewhat of an oversimplification because there are several levels of specialization to be addressed before the individual is indeed truly focused.

It is recommended that one of the first big decisions in your collecting life should be a decision on what you intend to collect. Will your collection be of insignia, medals, or of any of a multitude of other areas too numerous to mention? If insignia, for example, will it be cap insignia or will it extend to other badges? (Besides badges worn on the headdress, there are those on shoulder belt plates, pouch belts, waist belts, collars and buttons, as well as shoulder and sleeve titles and flashes. All these form part of a unit’s insignia and should be included in certain instances). If cap insignia are preferred, will you concentrate on cap badges or extend to include shako and helmet plates? Do you intend to confine your collection to other ranks (i.e. below the rank of a commissioned officer) or will you include those of officers (which are often different)? And so on. Similarly, if you decide on medals, will you choose campaign or gallantry examples? If the former, do you limit your choice to a certain geographical part of the world or to a certain conflict? Do you collect those medals awarded to only certain units, or indeed do you collect medals awarded to only one family? These are questions only you can answer. The list goes on to varying degrees of specificity depending on the type of artifact, but each decision has real implications to your collection and considered thought should be given. (Now that all this has been said, it would seem that most collectors tend to stumble into their specialty rather than by any conscious decision — perhaps because they have not gained enough experience to understand the chain of decisions that need to be made).

Once coming to the realization of what you want to collect, another consideration is the period or age at which you will start. More will be said of this later. If this still appears too vast an undertaking, an alternative is to devote the collection to a specific section of the army or a particular group of regiments, or indeed one regiment or one individual alone. For example, all those raised in, say, Alberta or some other province, or all Highland regiments, or even the regiment associated with the area in which you live are viable alternatives. Once again the choice is yours, but a word of caution — too large an undertaking can lead to frustration because limited resources causes a trade-off between breadth of interest and potential completeness of the collection.

Artifact Sources and Networking

The environment in which you will find yourself has been briefly discussed and now comes the question of where to obtain material. Military collectibles are to be found in the most unexpected places. Friends or family may have hoarded a souvenir in a small tin box or in the attic with other unwanted items (indeed the tin box itself may be a collectible). Items put away by past generations become forgotten and only come to the surface during a thorough attic cleaning. 'Junk' sellers have them, some antique and jewelry shops sell them and there are a number of dealers who cater specifically for the hobby. To a serious and experienced collector, sources of artifacts are as varied as the imagination. However the most common is still the collecting fraternity and the informal associations that grow through friendship. It is these contacts that ultimately lead to acquisition of better quality examples – either by notification by friends of the whereabouts of a particular item,or through trading, rather than by outright purchase. Probably for the advanced collector, relationships, be they with other collectors or indeed dealers (you can often get first call on an item if you have good rapport with them), provide the single greatest source for the rarer items.

Now the newly-initiated collector cannot hope to compete in this manner until experience has been accumulated and networks established, so it is well to find out at an early stage if there are others in your area who enjoy the same hobby. Make their acquaintance as they will be only too happy to talk about collecting and will display the gems of their hard-won collections. In addition, you may materially benefit from the surpluses (trading stock) within their collection.

In a more organized sense, there are a number of societies which cater specifically to the military collector and enthusiast. In Canada, there is currently two nationally-based collecting organizations which collectively boast a membership of over one thousand five hundred (see appendix). In practice however, one of these tends to concentrate its efforts in Ontario and Quebec while the other is more western Canada-focused. Each has local chapters in various communities. There are also many local or specialized organizations across the country as well as numerous international counterparts. While each of these groups has members with overlapping or common memberships to other organizations, each also has a unique set of members. It benefits the individual collector to belong to several of these organizations to ensure an adequate exposure, and the yearly membership fees are usually modest.

Most of the larger organizations meet regularly (at least in local chapters) in an informal setting and generally publish membership lists detailing individuals’ interests. Several also issue some sort of regular newsletter or journal that serves to keep the individual collector appraised of goings-on, as well as offering useful tips and information. Once you join a society you will find most members pleased to help newcomers, and normally will supply additional information on request. However, when you make a written request (there are still those out there who have chosen not to use the internet), do remember to include a self-addressed, stamped envelope:Honorary secretaries will go to considerable lengths to help you but you cannot expect them to pay for the privilege of doing so!

A further hint — when corresponding with other members, you should give as much detail as possible or enclose rubbings of the artifact, accurate drawings or photos with dimensions. This will often save answering queries and unnecessary correspondence.

There are many other collectibles sources available if one is observant and knows what he/she wants. Those most commonly utilized tend to be antique stores, flea markets, military shows and sales, pawn shops, conventional auction sales and more increasingly these days, on-line sources such as eBay. Museums also divest parts of their collections from time to time.

There are also dealers who specialize in military artifacts and regularly send out catalogues. These can be extremely fruitful and reliable. These specialist dealers are well aware of the value of military artifacts, and while bargains are scarce in this direction, the lists and sale results are usually accurate in estimating (and often setting) fair market value, and buying and selling trends. The other advantage of a reputable dealer is their ‘guarantee’ of authenticity with exchange of dubious purchases, no questions asked. But how does the beginner know whom to trust? The first step is once again to make contact with fellow collectors because word-of-mouth is still the best means of finding the good dealers. Do not rush into buying from any particular dealer. Study as many catalogues and inventory lists as you can obtain to see how prices compare. Above all be wary of the dealer who consistently offers a large number of scarce and rare items with prices tags that appear too good to be true. They probably are. If stocks of the more common artifacts were running out many years ago (which was often the case), ask yourself how it happens that there are now so many rarer badges available. As a parting note, if a dealer sells to you, or someone you know, a badge that proves not to be authentic, and will not immediately without question refund your money, or is consistently offering bogus material, drop him like the proverbial brick. These people can survive only so long as you, the collector, supports them. Now having said all that, reputable dealers can also be one of your greatest allies. Once they learn of your own particular interests and your own trustworthiness, they will remember you and can often offer exceptional items to you, sometimes at discounted prices, and ahead of the general collecting public.

Lastly, the most lucrative sources of collectibles is and always has been the general public. This is still probably the single greatest untapped source of material as most people do not understand the value or significance of what they have in their own homes. To them it is often just interesting junk or clutter to be discarded. So garage sales and estate auctions can often prove very profitable. A hint though — when going to a sale of some sort, it pays to get there as early as possible. Veteran collectors know this and will use any reasonable method to get a jump on the competition, even to the point of finding a way of gaining access prior to the official opening of the event.

Many of these avenues are advertised and it is just a matter of patronizing each event or individual dealer, but you will find that as your interest becomes more serious, you will begin to always be on the lookout for opportunities or that lucky find, with one segment of your brain permanently centred on the hobby. You always get lucky from time to time but then isn’t luck usually the point where opportunity and preparedness meet.

The Auction Sale

One source deserves special and more detailed mention, this being the dealer/auction house. In the past several years these institutions, and in particular eBay, have gained a very prominent place in the military collecting environment. In addition, by participating in these sales and/or subscribing to mail order auctions (a rapidly-rising phenomena in Canada because advantages to the auctioneer are obvious — less overhead, smaller inventories and a chance to make profit from both buyer and consignee through commissions), one can pick up a considerable amount of knowledge and information. There are several well-known and reputable auction dealers that offer regular sales to Canadian military collectors and these should certainly be considered.

Because of an ever-increasing population of military collectors, it is becoming more difficult to find the scarce, desirable or good condition items in shops and at specialty shows. Most of this sort of material is now coming onto the market when old established collections are broken up either through veteran collectors changing interests, deciding it is time to sell out, or passing away. It is generally on eBay or in the auction room where these treasures appear. If this happens, not only are all collectors given an equal opportunity to bid for these items, but in this day and age, you do not necessarily have to be present to do so. Further, with the increasing numbers of auction sales happening, auctions are now tending to set the price of items. Once again, eBay, by its popularity, is now becoming the reference point or forum by which the market establishes the value of an item. No one can argue with a realized price when that price is determined in open bidding.

Yet, there still appears to be many misconceptions regarding military auctions, how they work and how to go about bidding effectively. There is really no deep secret to participating in an auction sale, other than knowing what to expect and using common sense.

Depending on the auction company and the merchandise being offered, there are several types of auctions. They may be formal in-person only sales, mail bid auctions, silent auctions, specialty auctions by invitation only, the internet auction, or any combination of the preceding. For the most part, excepting on-line sales, all are generally held on the premises of the auction company and are presided over by an auctioneer (either an employee of the auction house or a contracted individual). In almost all instances, there is a requirement that the prospective bidder register in advance in some fashion. This is to the advantage of all concerned as it speeds up administration and maintains momentum on the floor.

All auction houses publish catalogues or lists of lots well in advance of sale dates. These are usually sent to clients by mail or email through subscription or if the client is well known to the auction house, or are available on line. Once you receive the catalogue, you should carefully check the following information.

- The date and time of the sale. Nothing is more frustrating to a collector than reviewing the catalogue, choosing lots to bid on and actually placing your bids (in the case of mail auctions), only to be informed that the sale occurred the hour or day before.

- Carefully read the ‘conditions of sale’, including the small print. These are usually found inside the inside cover or on the first page of a catalogue or somewhere in the lot description. They set the rules of the sale and will be referred to in any dispute or disagreement. You, as the bidder, are solely responsible for understanding these conditions and how they apply to you. Because you are, in effect, entering into an agreement to purchase, it is in your best interests to know these conditions. For your protection, as well as the auction house and consignee.

- Review the glossary of terms, list of abbreviations and grades of condition. Each auction house has its peculiar idiosyncrasies of vocabulary and outlook on condition of items. The terminology used can be quite specific and equally mind-boggling to interpret. Likewise, in any description, you are relying on the opinion of the appraiser at the auction house to give a clear portrayal of the item, so it is once again in your best interest to understand where the auction house is coming from, so there will not be any undesirable surprises.

- Last, and as is true in most similar circumstances, it is always ‘buyer beware’.

After reviewing the item, you have now decided to participate in the auction. Assuming mail bids are accepted, you may now submit a mail bid, arrange for a private agent to bid on your behalf or you may attend the sale in person. Or as is the case with the internet, you place the bid yourself. In the case of a traditional auction, you contact the auction house and register your bid. All auction houses require that a submitted mail bid be in writing (either by post or email) and often signed by yourself. This is for the protection of both you, the bidder, and the auction house. A written record allows the auction house to record the exact time of receipt, which becomes important in the event two identical bids are submitted. In the case of traditional auctions, once the mailing deadline has passed the auction house staff will review the bids and determine the highest mail bids for each lot. A member of the auction house staff will then act as ‘agent for the client’ for each of the highest received mail bids. It is important to realize that the auction house will only act for one mail bid client per lot. Generally speaking, the auctioneer will open bidding at the second highest mail bid realized, thus offering an opportunity for the winning bid to purchase at a lower price than his/her maximum allowed bid, assuming input from the floor itself does not prevail. As with any auction, ultimately the highest bid, whether received by mail or from the floor, will be successful in purchasing the item. A few simple rules when bidding by mail or internet should be followed.

- Read the conditions of sale carefully.

- Sending in an early bid will set precedence although there is also value in internet bidding to wait until near the end of the auction, so as not to run up the price.

- Fill out the mail bid sheet completely and legibly, and accurately. If the auction house cannot read the form, or if there is any doubt, they will not record the bid, nor can you expect them to contact you for clarification. And only you are at fault should you inadvertently submit an incorrect bid.

- Be aware that there are usually additional charges associated with your actual bid – buyer’s fees, provincial sales tax, GST, shipping and handling charges, mail registration or courier charges, etc. It is well to be aware of these additional costs as they can add significantly to the overall purchase price.

- It is prudent to confirm your bid. Contact the auction house by telephone to make sure they have received and recorded it. The cost of the call is insignificant when you consider the consequences of the house not receiving your bid, and most houses will gladly furnish this information. As an aside, some auction houses will make mail bids public, upon specific request, up to the mail bid deadline. It is in your interest to determine whether this policy is in effect. If that is the case, then it is not necessarily prudent to place an early bid for all to see. Rather, it is better in this case to wait as long as possible to submit, checking first to see what bids have been submitted to that point. However the danger is that your written bid (usually faxed in this case) may not be received by the auction house before the deadline. In that case, you will lose out. If you choose to delay, make your bid submission by phone and then follow up in writing with a fax, but again, confirm the fax.

- Don’t be afraid to withdraw a bid. If you do not want the item, for whatever reason, telephone or fax the auction house and advise them. But, obviously, do so before the auction and then follow up with a confirmatory letter if you phoned.

- Don’t submit an unlimited bid. This is a dangerous practice and most, if not all, auction houses will not accept such bids. If you are that desperate for a particular item, it is suggested you attend the sale in person. In that way, you can personally control your bidding.

The second method of participation in an auction sale is to contract a private agent. You can certainly use a relative, spouse or friend to bid on your behalf, but remember these individuals are generally not that knowledgeable about military collecting. In their ignorance, or if they get carried away with ‘bidding fever’, you may end up making a much larger investment than anticipated. The other alternative in this case is to hire a professional to act on your behalf. Generally this would be a dealer, a professional appraiser or recognized military collector of experience. These people are knowledgeable and are contractually paid to represent your best interests. However, you do have to pay them for their services. The choice is yours.

Lastly, you can attend the sale in person. The advantages with this option are obvious. You can review the lots first-hand, you can gauge the mood of the other bidders, and most importantly, you control your own bidding at all times. A few suggestions if you plan on personally attending a sale.

- Go early. Register and find a good seat with a view (where the auctioneer can clearly see you).

- Check to ensure the lots of interest are still in the sale. Lots are sometimes withdrawn for various reasons.

- Check to ensure the lots are as described. These descriptions are based upon the opinion of the auction house or a professional appraiser. Errors can occasionally creep in either through lack of knowledge, experience or observation. Buyer beware!

- Be wary of what you overhear. Some bidders will try to dissuade the competition from aggressively bidding by expressing doubt to any who can overhear, regarding the quality or genuineness of articles prior to the sale.

- When bidding, indicate in a way that the auctioneer can see. There is nothing to gain by being overly subtle or secretive, but there is a lot to lose if the auctioneer either misses your signal or misunderstands it. If you feel the auctioneer has missed your bid, the most expedient thing to do is to wave your catalogue, raise your arm, or call out your registration number.

- If you feel an item has been sold without considering your bid, inform him immediately. If the rules of the house permit it, he has the option to re-open the bidding.

- Sometimes a flurry of bids will be placed simultaneously. In this instance, it is left to the auctioneer to recognize one bid. If this occurs and it is not your bid that is recognized, be patient and observe what happens. Overzealousness on your part by insisting on having your bid recognized could lead to you bidding against yourself. It is better to wait and observe the flow, and then to bid at the appropriate time.

At an auction, everyone has equal opportunity to purchase an item. Yet people sometimes feel the auctioneer is exercising preference for certain bidders. Nothing could be further from the truth. No auctioneer practicing this policy would last long in the marketplace. Besides, the auctioneer makes his living from commissions on prices realized. It is not to his advantage to minimize bids. The auctioneer can control the tempo of the bidding, but has no legitimate way of ignoring valid bids.

Likewise, individuals are sometimes intimidated if they perceive that they are bidding against a dealer. They often feel that the price will be run up by the dealer. Once again, this is highly unlikely because the dealer is in the business of making money. He/she is not going to pay inflated prices for items that they will be placing on sale in the future. At best, the dealer may have a clearer idea about the value of an item and will be bidding accordingly. If you play the game of trying to run the price up on a dealer, it will ultimately be you that suffers.

Once the sale has been completed, you are, of course, expected to pay for your purchase. Depending once again on the conditions of sale, this may be done immediately in person or by email using conveniences such as PayPal, by mail or at some later date, as agreed to by the auction house. Usually when the next sale catalogue is published, there will be a page included that lists the prices realized of the previous sale. This is a good thing to retain as it provides a history of the value of each of the offered items, which can be useful in future dealings.

Once an item has been appraised and is assigned a lot number, it is usually sealed in a plastic envelope (providing it is small enough). This is then sent to the successful bidder (if not attending the sale) in this condition. Should you find that the item is not as described, or if you are unhappy with it for any legitimate reason, make contact with the seller/auction house. Usually they will accept the item back if the concern is legitimate. In that case, simply return the item still within the package. In this way, there is some assurance that the item sent back is the same as shipped. Unfortunately there are those out there who will use an auction sale as an opportunity to fraudulently benefit. These individuals (also known to the author as ‘low-lifes’ or ‘scum’) will substitute a reproduction for the genuine and return it stating that the lot was a reproduction. In this way, they not only obtain a genuine article but at no cost to themselves. By leaving the item in the sealed envelope, it minimizes the chance of this occurring. At any rate, most auction houses will only accept goods if they are returned as shipped.

Auctions have proven to be good for military collecting. They allow recycling of premium material through the collecting community and they provide insight into the value of items, if not actually setting value. For the purchaser there is an insurance that should the object be found defective in some way, the auction house will refund or otherwise compensate. This is not always the case with other sources of artifacts. This also holds true for the specialized dealer. However, as with anything else, educate yourself before participating. In that way, the experience should be positive.

Learning the Hobby/Education

Throughout the preceding, one should by now be getting a vague inkling that experience and knowledge are most important. If you are to experience the most from this hobby, it is critical to know your subject area as well as your objectives — it is usually far more lucrative to research first and buy later. Therefore, before you commence collecting and always during it, continue to learn as much as you can about your hobby. It will help you to avoid making later mistakes which could prove expensive and frustrating.

The question is then, how to gain this knowledge? Surprisingly, as alluded to earlier, most learning comes about without you actively being aware of it. Individuals generally try to find something about their purchases at time of purchase and these little bits of information are assimilated. These efforts coupled with knowing the parallel experiences of collecting colleagues, will accumulate and start to fall together in a mutually supporting fashion. Before you realize it, you are somewhat of an authority. Why not help the learning process along through organized research and study? Why wait?

Where there is a need or desire for more formal research, it is simplest and quite accurate to say that collectors use the same sources as professional researchers. However their approach tends to deal more with the minutiae of the subject as opposed to broader issues. This comes about because of the detail needed in determining exactly the type of artifact you have as well as the history around the item. But don’t fall into a trap of focusing too much. Initially, one would think concentration on the purely military aspects of an area would suffice, however this author has found it more beneficial to broaden your scope to include an appreciation of the social and political aspects of the period you are researching. By keeping efforts broadly-based, an understanding of the evolution of specific artifacts and the causal factors that brought about the need for such an item can be gained. This in turn will give a greater appreciation of the item in question and could lead you in new but related interest. It also prevents boredom from setting in.

It is in the best interests of the individual collector to build up and maintain as complete a personal library as possible. Your library should include not only historical information pertaining to your particular interest, but also records of asking and selling prices, histories of related artifacts as well as a complete and up-to-date inventory of your collection (for insurance purposes, if nothing else). It also does not hurt to have some general histories of good quality. By having this information close at hand, it provides a ready reference to enable prudent purchasing, trading and selling. It also allows you to better chart the course of your collecting strategy. To what detail an individual wishes to research his hobby is a personal choice, but remember that those collectors with greater knowledge tend to have the best collections.

It seems too often we Canadians let others produce all the main information volumes on Canadian military artifacts. While this has been changing over the last few years with the recent explosion of published material on Canada’s military past, many of the most popular or 'standard' military collectibles sources have come to us from French, British and American authors. Other nationalities appear to be interested enough in Canadian military heritage to formally document it, yet the vast majority of collectors of Canadian military items are Canadian. Interesting!

Editorializing aside, for the collector of military artifacts there are several useful books that will answer most everyday queries (see appendix for a listing). There is at present no one text adequately dealing with the whole of the Canadian military collecting scene, nor will there likely ever be one. There is just too much to cover in a single work. There are those who have attempted this broad approach, but they are rare and generally leave too many gaps to be used with any confidence or convenience. The other unfortunate point is that many of the best sources are now out of print. But do not despair — copies can usually be found in used book stores or in the hands of more experienced collectors. Assuming you will only be using the information for your own personal use and that the book is out-of-print, there is always the photocopier.

For those who choose not to develop a library, several of the main institutions concerned with military history have extensive libraries and, within certain guide-lines and limitations of staff, usually allow serious students and collectors access to them. These institutions include museums — public and specialized (e.g. regimental museums), military historical societies, universities and, of course, national, provincial and civic archives. Usually an appointment will be necessary so that it is essential to write or telephone in advance to check the position. Written inquiries are also dealt with but in these days of limited staff and facilities there is likely to be some delay in receiving a reply. Regimental museums, in particular, are frequently staffed by part-time curators whose time is usually well-filled and replies to queries can be rather slow in coming, while, for basically the same reasons, you can expect a minimum of four to six months for response from the National Archives. In some cases these institutions will charge a nominal fee for a query. If information is being sought by letter the request should be as specific as possible. If identification of an object is sought, once again a photo or competent sketch is more or less essential; verbal descriptions can be very vague, confusing and time-consuming.

A word of caution, though, concerning museums. Unfortunately it is a fact that many museums harbour a basic distrust of the average collector, which can range from active hostility to passive apathy. There are several reasons, but most tend to centre around the security of their collections and the fear that a collector may present a threat. At the very least, they often see individual collectors as being conflicts of interest. It is also a fact that many military collectors harbour similar negative feelings towards museums, once again for a variety of reasons. These reasons can include a perception that artifacts preserved by museums are seldom displayed and therefore are, in essence, lost to the public, or that the museum represents a formidable competitor for artifacts. Whatever the reasons on either side, this negativism is present and can only be overcome with an appreciation of what each group can offer. In those cases where simple and honest communication is attempted, it is the experience of this author that mutual trust is developed leading to a mutually satisfying relationship. Both sides must recognize they are allies and not antagonists. Thankfully, this mutual animosity is steadily decreasing.

Addresses of these various museums and other organizations can be found in many publications available at most libraries (some of the main ones are listed in the appendix).

Lastly, there is once again, the internet. When this booklet was initially written, the internet was just beginning to gain its popularity and personal computers were the exception rather than the rule. Now, as anyone who uses the internet, can readily appreciate, it has become one of the major sources of information in our society. Collecting militaria is no different and the information available by this vehicle is only limited by the imagination of the user. However, it should be emphasized that a significant portion of that information comes from second, third and greater generations of investigation. What this author is trying to say is that the information presented may be flawed or inaccurate. Without the ability to confirm such, can lead one to the wrong conclusions.

Military Artifacts

Variations in Military Artifacts

Depending upon the individual, variations in a particular type of artifacts can be critically important or an interesting oddity. Generally, though, variations, even those that are subtle, can be significant to identifying and/or determining the uniqueness of a military artifact.

Throughout recorded history, military forces have always affected some means of identification to differentiate friend from foe. Generally, this has been through the adoption of some commonality of dress. Hence the term, “the uniform”. Starting very simply in early history, this form of identification quickly developed, in many cases, into quite elaborate costumes. Uniforms themselves have also invariably been adorned with various forms of additional markings or ‘insignia’ — either as embellishment of fashion, or to further identify the wearer’s specific unit, specialty and/or status (i.e. rank). Further, most insignia and uniforms tend to exhibit idiosyncrasies of design which relate to the specific history, function or traditions of that particular unit or corps. These traditions encompassed within the evolution of uniforms and insignia are now widely utilised in research, by historians and collectors alike.

Over the years, vocabulary surrounding the description of items has become, in many instances, very specific and unique in their meaning. For the purposes of this work, more common names will be used. While less precise, they should nevertheless suffice in any description here. However, a few points of clarification regarding insignia should be made. Insignia are generally categorized into a few broad categories. First, and probably most universal, are those insignia worn on uniform headdress. These are generally referred to as the ‘cap badge’ or in some special cases, the ‘helmet plate’. Of various construction, invariably both metal, cloth or combination of both, these are a revealing form of identification. Secondly, you see badges similar to the cap badge, but worn on the collar. These may be miniatures of the cap badge, or a completely unique design (in some rare cases, cap and collar badges are completely interchangeable). Depending on symmetry and direction of design, there may be distinct variations specific to the right or left collar. Thirdly, most uniforms display some sort of shoulder marking or ‘shoulder title’. Once again of either metal or cloth, they usually spell out in some fashion, the unit and nationality of the wearer. Also worn on the sleeve, but generally lower, or on the breast of the uniform jacket are various further identifying patches or badges, again of varied construction. It is also common to observe insignia devices incorporated into belts or webbing, and can include waist or cross belt buckles and plates. Lastly, there is a great variety of rank devices that can be found in various forms, depending on period of usage, which are usually found on either the top of shoulder straps, on the cuffs of the uniform jacket or attached to the collar lapels. These differences once again reflecting their age and then-prevailing military dress regulations. One other instance of unit or corps insignia are those seen stamped or printed on accoutrements and personal kit. While not part of the uniform itself, these obviously indicate unit affiliation or ownership. It will be seen that the majority of insignia described later fall into one of these categories.

Lastly, variations of military items, especially insignia, come about through differences in the manufacturing process, more of which will be discussed later. While on the surface, these may appear to be trivial, changes in construction often give clues to the provenance, and hence, history of an item.

Cost Estimations

Most any collectible item has three values – one intrinsic, the second sentimental or emotional and the third, historical. Intrinsic value is whatever the open marketplace will bear, and is based on the value of the compositional material in the item, as well as its relative rarity. This aspect of value can usually be estimated with a fair degree of confidence. The same can be said for historical value. However, sentimental value also affects the final cost of an item. This latter value is obviously harder to determine because emotions are involved which make each case uniquely individual. This is especially true of the auction environment.

Currently, there are more and more individuals getting into this hobby. This has had tremendous impact on available supplies, which, in turn, translates into higher prices. It is safe to say that in the past ten years alone there has been an inflationary spiral in the cost of many military artifacts of at least one thousand percent or more, and unfortunately this trend appears to be increasing ever more rapidly.

This has both positive and negative implications. The positive is that increasing values have resulted in more individuals buying and selling artifacts (more collectors have been getting into the selling or dealing game). Coupled with this is the fact that with the increased prices realized, collections are being broken up and sold for profit at ever-increasing frequency. This provides collectors with an increasing rotation of new material in the marketplace. While many items are still in short demand, this ever-changing rotation or resurrection is the life blood of many collectors.

Obviously, the more people collecting, the less there is to go around, and prices again rise. In the past one was often able to negotiate the price of an item with the seller. This is harder to do now because most retailers, 1) have not developed a relationship with the newer collectors, and 2) understand there is a strong buying market present which results in rapid sales at original asking prices. Once again, the value of collecting relationships based on friendship should be obvious here.

It is hard to give any appreciation regarding prices, due to the large number of factors affecting the price, and it is probably also dangerous. Apart from the normal supply and demand effects already mentioned, there are more intangible factors. You see regional differences in prices. Artifacts pertaining to units with long associations in particular communities will usually realize higher prices in those communities. Veterans may wish to rekindle memories years after their service and will buy up available stocks, thus depleting inventory. A collector may be prepared to pay a price well above the norm for a specimen he/she particularly wants in order to fill a gap in his collection. Something as trivial as two collectors harbouring mutual animosities will often allow stubbornness to rule bidding strategy. Some collectors just plain don’t like to be outbid. The result of all these is that prices are driven unreasonably skyward — at least in one instance — but then the precedent has been set. Once again, the rule of thumb is to research the purchase as much as possible, discover the trends and then reconcile this information with what you are prepared to spend to gain the piece. Then stick to that price!

There are a few reference catalogues now on the market which list price approximations for certain classes or periods of artifacts. While this author is not in favour of them because of the inaccuracies that must arise due to changing situations and environments, they can be useful as an approximate or relative indication. As a guideline, especially when there is close agreement between two or more, they can be helpful. If you feel you must use them, remember the factors that affect price. Even after warning of the danger of potential inaccuracies and therefore false perceptions in using these guides, it is has turned out in practice that, depending on the reputation of the author, dealers will often base their asking prices on these estimates. Therefore, look for trends and approach the subject with care.

The question is often raised — “When is the right time to buy?”. There is really no other answer than to say it depends on how badly you want the article, its sales history and your ability to meet the sales price. A particular item, unless one of a kind, should eventually turn up on the market if you are willing to wait. But you might have to wait a long time, and when the opportunity again presents itself you may not then have the resources to acquire it. To be sure, it will be more costly and if present trends continue, there will probably be more competition for it. But on the plus side, by waiting you appreciate the game better, know the realistic value of the item and therefore can discriminate with confidence, (thus utilizing your resources to the maximum) and the item will mean that much more to you when you finally have it in your possession.

Factors affecting costs and identification criteria

While everyone can readily think of exceptions, much militaria tends to be materially insignificant. Value comes from the relative rarity of the item as determined by either the collecting community or individual collectors. In the case of individuals, the significance of an item to a personal collection means that the individual may be willing to pay far more than its intrinsic worth just to ensure it is captured. Apart from the economics of supply and demand already mentioned the other factors that are always taken into account by collectors when valuing an item are as below. These factors not only derive the price but are also very useful in determining the origins of the article.

Fortunately many military items have points of identification which facilitate the individual in determining age. These points of identification may be as simple as a government stamping indicating age and origin, or may have more subtle indications based on design. In the case of the former, it pays to look over the artifact very carefully — they are often hard to see. When dealing with these design differences, certain conventions need to be known.

Generally when discussing Canadian military artifacts, collectors divide them into periods of age:Victorian (1855-1900), Edwardian (1900-1914), World War I (1914-1920), the Militia years (1920-1936), World War II (1936-1945), post war King’s crown (1945-1953), Queen’s Crown or pre-unification (1953-1967 +/-) and post-unification (1967 +/- to present). These periods are somewhat arbitrarily defined and are based upon some significant event in Canadian military or political history. But in practice the boundaries are flexible depending on the exact history or circumstances of the units involved. Similar distinctions, with departures due to unique histories, are used in the United Kingdom and most other Commonwealth countries. In the case of other European countries, time conventions are usually closely tied to the then-reigning monarch.

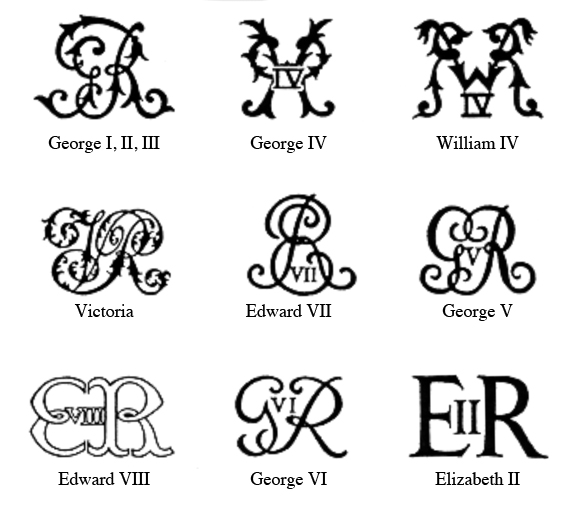

As can be seen the above ages approximate significant wars or the reigns of British monarchs. In the former case, differences in design occurred because of a need to rapidly mobilize large armed forces to meet the threat of war. Many new units and equipment in these times are developed and as such provide an identifiable subset. In the latter case many British and Commonwealth (including Canada) military artifacts, and especially insignia, incorporated some emblem of the currently reigning monarch, most commonly unique crowns or royal cyphers (monarch’s stylized initials) in their design — features which are retained when other details are altered. These signify loyalty to the monarch. The shape of the crown and cypher changed whenever a new sovereign came to the throne and are useful in giving a rough date to an item. In the case of Victoria, she adopted a design now known among collectors simply as the Queen Victoria Crown (QVC). Succeeding male monarchs chose the Tudor crown or King’s crown (KC) while Elizabeth II has taken the St. Edward crown or Queen’s crown (QC) as her own. The Queen Victoria crown actually comes in several similar but slightly different patterns but is readily recognized by its flat-topped or square appearance. Of course, some designs do not have a crown or cypher present. In these cases, it becomes more problematic to determine age and one must look at other clues.

Also present in many designs is the personal cypher or monogram of the then-reigning monarch. While these show variations, most tend to revolve around a common theme. Regiments and units having connections with the monarchy through the Commonwealth of Nations, or earlier, the British Empire, often incorporated the Royal Cypher into the design of their insignia and equipment.

It is a general truism (but many exceptions) that the older the item, the better it was constructed. Early badges and other metal items tended to have extra care given to their manufacture. The finish is better, extra time was spent on the edge and the like. At the very least, older badges often have developed a very nice patina (due to oxidation) on their surfaces that only age can produce. Difficult to describe, but as a collector becomes more experienced, this patina is easily recognized.

Similarly the design of the fasteners on the reverse of the item show distinctions of period. In the case of early Canadian material, fasteners tended to be either bend-back tang (flexible wire ribbons) or machined lugs with squared or hexagonal edges. (A lug is a looped device that is soldered to the back of the badge and passed through the material of the headdress where either a brass or plastic split pin or thin wedge of leather was pushed through the loop to hold the badge in position. More recent designs tended to incorporate simply a bent wire lug format or a slider (a narrow flat bar running parallel with the badge but standing slightly away from the back which slips into a slit in the material of the uniform item) type of attachment. Fasteners can also be friction or screw backed pins. These, along with the slider type, are more common in custom made badges or more modern examples. Presently, many metal badges are seen mainly with the slider or a pin and holder arrangement. The last common variant of fastener seen is a screw pin arrangement. Also with changing times, uniform design altered, necessitating the design of certain unique fasteners to accommodate the changed patterns.

When confronted with an article of unknown design, one of the first things to do is to determine its nationality. The presence of a crown will indicate the item came from a monarchist country. This in itself will narrow the search somewhat but this can be taken further. In the case of British and Commonwealth countries, crown designs will be as described above. In the case of other European countries, crowns will be of different style but nonetheless usually unique to that monarchy. Also look once again for a cypher. It too will be distinctive. The third thing to look for is some sort of national emblem. It can be an official coat of arms or some more common talisman readily associated with a particular country. In the Canadian case, predominant in the design of many insignia is the inclusion of a maple leaf, a beaver or both. Other conventions, by way of example, are the United States, an eagle; British, a lion; Australians, a kangaroo; New Zealanders, fern leaves; Irish, Gaelic writing, and so forth. Another method that sometimes bears fruit is to look at the design of the badge itself. Certain basic designs are often favoured by particular countries. For example, the maltese cross can be commonly found in German or Maltese artifacts, however the Maltese version of the cross is usually distinctive from that of the German version by the narrowness of the cross’ arms as they come together at the centre of the cross. Regiments and the such (especially the British) often incorporate references to some significant event(s) into the design of their badge. This may be as simple as a listing of battle honours or some more obscure emblem representative of a particular campaign of which the unit is proud. For example, the various versions of the Royal Highland Regiment (The Black Watch) cap badge often have a sphinx illustrated, reflecting the time spent by the regiment in Egypt during the Napoleonic Wars. The design may be indicative of the origins of a unit or, in the case of specialty corps or branches, the unit’s purpose in life is somehow shown. Obviously, at this juncture some knowledge of history stands the collector in good stead. Lastly, many manufacturers stamp or indicate their name on the reverse of an item. In the case of Canadian manufacturers, the list is relatively short and has remained somewhat constant. So look for that. Of course, the situation is complicated somewhat by the fact that Canadian units serving overseas often had their insignia, etc. made by British manufacturers.

Some Manufacturers of Canadian Military Insignia — Past and Present

|

A. W. Gamage, London Alexis David, Paris Alfred Constantine, Birmingham Army and Navy Co-operative Society, London Birks Ltd. Botty and Lewis, Reading Brown C. A. Hodgkinson, London Caron Brothers, Montreal Chauncey Maybees Cooke Creighton’s D. A. Reeson D. E. Black, Montreal D. R. Dingwall, Winnipeg Dominion Regalia Eaton's Ltd, Toronto Ellis Brothers, Toronto F. W. Coates G. Barron, Folkstone George F. Hemsley Co. Ltd, Montreal George H. Lees George Jamieson and Sons, Aberdeen

|

Goldsmiths & Silversmiths Co. Ltd, London H. Ford, London Henry Jenkins and Sons, Birmingham Hicks and Sons, London Hobson and Sons, London J. B. Bailey J. R. Gaunt and Sons Ltd, Birmingham J. R. Gaunt and Sons Ltd, London J. R. Gaunt and Sons Ltd, Montreal J. W. Tiptaff and Son, Ltd, Birmingham Jackson Brothers, Edmonton Jacoby Brothers, Vancouver Kinnear & Desterre Marsh Brothers, Birmingham Maybees McDougall, London Miller Brothers, London Moore, Taggard and Co, Glascow O. B. Allen Patterson Brothers Reich, Folkstone Reynolds Roden Brothers |

Saqui, London Savoy Tailors Guild, London Shirley Brooks, Woolwich Sidney Barron, Folkstone Smith and Wright, Birmingham Stanley & Aylward Strickland and Son, London The Jewellers Co, Haslemere, Surrey Thomas White, Aldershot Townsend, Birmingham Twigg, Birmingham United Service Supply Co, Rochester Vaightons, Birmingham W. J. Dingley, Birmingham Wellings Wheatley Wheeler and Co, London William Anderson and Sons, Edinburgh William Scully R. J. Ingles, Montreal |

The above has discussed methods to determine the nationality of a military artifact. It often happens, though, that a collector comes across an older item he/she feels may be military in origin. However, because of similarities in use and design (the military has always contracted out to civilian manufacturers), the article could just as easily be civilian in nature. To overcome this and establish ownership, the Canadian and British military adopted the convention of stamping or painting an identifying mark to signify government or military issue. This device is commonly called the ‘Broad Arrow’ (if British in origin), or the ‘C Broad Arrow’ (if Canadian). Simply described, the ‘Broad Arrow consists of a simple line arrow having widely spaced arrow points. Patterned after the British, the ‘C Broad Arrow has the arrow with a capital ‘C’ in serif pattern surrounding the arrow as a whole. The presence of this mark on an artifact definitively identifies it as government issue.

Manufacturing Methods, Materials, Variations

Fortunately, for beginners there are now available a number of reliable books with clear illustrations of the various articles and good descriptions. However the book which illustrates every possible example made will probably never be written. There have been, are, and always will be variations on a theme. This is most especially true of insignia, which will once again be concentrated on in this section (medals, which seen in variation at times, tend to be more consistent as they are generally struck at the order of a particular government with strict attention to detail — there are, of course, exceptions to this. The main variations seen in medals are the style of placing the recipient’s name on the medal; different script, depth of stamping, etc.). Regulations may define a badge, but the manufacturer may have deviated slightly, or the regiment or battalion may have claimed an exemption to the rules. Different manufacturers at different periods of time often will use slightly different stamping dies and different metal alloys. The usual item may be of brass but it is not impossible to find variants of bimetal form, that is, with parts of brass and white-metal or indeed, completely constructed of white metal. In some cases the badge may not even be recorded and it has been known for a regimental museum to deny the existence of a proved genuine badge of that unit. Thus the badge being offered may well be totally genuine but just slightly different; the spelling of the name may vary slightly; the position of one feature may be slightly different. Also personal preference or convention of a few may cause an unofficial piece of insignia to gain respectability through use, and therefore become ‘official. In the end it must be a matter of opinion until research from old photographs and other sources proves provenance one way or other. All this will affect the price of the item.

In the case of insignia, brass has always been the commonest material used but external pressures have sometimes forced changes. In 1942, during the Second World War, in order to conserve stocks of metal, several badges and other articles were manufactured from plastic. These plastic examples were basically copies of the original metal form and were produced in silver, bronze, black and dark-brown colours. In the early 1950’s another type of material, Staybrite, with a rather cheap and shiny look to it, was often substituted for reasons of economy. This trend towards economy has continued to this day, where you now see a prevalence of cheap machine-made embroidered examples.

Regular force units may have had their insignia in brass or gilt metal for officers, while the militia, a form of reserve force, often had theirs in white-metal or silver. In the case of other ranks the badges were normally die-stamped from a single piece of metal but those for officers were more elaborate with the central or regimental insignia made separately and held in place by wire or small rods passing though lugs on the back of the badge. Officers have generally been permitted to have better quality insignia made. These are simply gilded or bronzed, in some cases made of silver, or a portion of the badge silvered, or elaborately manufactured by jewelers. Hence the difference between officer’s and other ranks’ badges. 'Off-duty' wear or undress officers' badges also commonly show an embroidered variation.

Most badges and medals tend to be die struck or stamped. This means a piece of medal is laid over a die or mold of some sort upon which a reverse rendering of the design has been engraved. The piece of metal is then stamped with a weight of some sort, causing the pattern of the design to be imparted into the piece of medal. The stamping may be seen on only one side, utilizing only one die, but more commonly, a double die arrangement of some sort is used, causing the design to be seen on both sides (the reverse is usually much cruder and does not show the sharpness of the obverse). Artifacts are also sometimes cast, utilizing a mold and molten medal. In this case the product is often much cruder with the reverse being without any design. Care should be taken by a collector when he/she comes across a cast article because this was not the preferred method of manufacture. Copies of rarer badges have often been produced this way as it is cheaper and fairly simple to accomplish. Notwithstanding this, there are examples of authentic material that was cast. Once again, the acquaintance of a knowledgeable colleague can help here.

Apart from the badges and medals of the armed forces there are many other types, both official and unofficial, including those known as Sweetheart badges. These are essentially decorative civilian versions of the official badge and while often similar to the original article, have never been officially sanctioned. As a result their specific characteristics will never appear in catalogues. The copies are usually smaller than the actual service badge (occasionally they are the collar insignia that has been ‘improved’ in some manner). Some are enameled, some had gold, silver and even diamond fittings and most have pin back fasteners. It is safe to say all have some embellishment over the original article they portray. The sweetheart badges were those worn by wives and sweethearts as mementos of brothers, husbands and boyfriends serving in the forces and should not be confused with the original article. Paramilitary organizations will also affect military type designs in their insignia which further confuses the issue.

Condition is important and usually one of the most discriminating factors in determining value or desirability. Generally military artifacts are given some sort of condition description by dealers and auctioneers, but these tend not to be universally consistent. A trend of late, however, is the move toward the conventions utilized by coin collectors. If you find a seller does not use this type of convention, it would be beneficial to familiarize yourself with the criteria that he does use or buy a few small items and compare the condition with the descriptions he gives.

It is not unknown for articles to have been converted to some other use. For example a badge may be remounted as a brooch or napkin-ring. In such case the original construction is altered in some manner. A rare badge may have been rescued from such use and re-converted and as such can be considered less desirable than an unchanged example.

It is good policy to expect every piece to be wrong and then convince oneself that is right rather than the other way round. Don’t let the emotions of discovery override your logic and objectiveness. Look at the fastenings and fittings and see if they are likely to be replacements. Examine the piece for breaks and repairs. Check the backing of the item — this is often more revealing than the obverse. Pay close attention to the small details. A good magnifying-glass is well worth using when examining a specimen for there may be small defects or inconsistencies not visible to the unaided eye or inconsistent with the type of manufacture. Check for a patina in older examples or polishing wear that would be consistent with an article of that age. Carry detailed descriptions or catalogues with you to help in your appraisal — don’t necessarily trust to memory — after obtaining many examples, patterns of design tend to blend into each other and when your collection gets to the point where you are looking at variations, you can easily become confused at what you already own. Be careful and take your time. If you don’t know, ask a more experienced collecting colleague.

Commonly Used Terms for Grading Condition of Military Artifacts

- Mint or Uncirculated: As issued, in pristine condition

- Extra or Extremely Fine Plus (XF+): Almost mint, some faint surface markings or hair line scratching

- Extra or Extremely Fine (EF): First class condition, with some slight scratches or abrasions, no sign of wear

- Very fine (VF): Surfaces clean and distinct, some scratching or contact marking, slight wear to highlights

- Fine (F): Surfaces clean and distinct, but showing signs or heavier wear, some “dints”, contact markings, abrasions, scratching, or a combination of all. Highlights a little worn

- Very Good (VG)

- Good (G)

- Worn: Surfaces worn, either by neglect or heavy polishing, heavily abrased, and or, contact marked, highlights deeply worn

- Edge Knocks (E/K): Abrasion or damage to edge or article , due to dropping or mishandling; most often used for medals

- Brooch Marked: Medal having been mounted for wear as a brooch, but later reconverted back to its original form, but the marks of the mounting are still visible

- Pitting: Damage caused to the surfaces due to contact, corrosion, or faulty metal, casting or striking

One can see from the above terms that there is great latitude present in assigning a condition to an artifact. To overcome this in part, it pays to familarize yourself with the biases of the appraiser making such calls. This can be done by attending sales and shows where artifacts are described as above. By comparing the actual item with its description, greater insights can be gained.